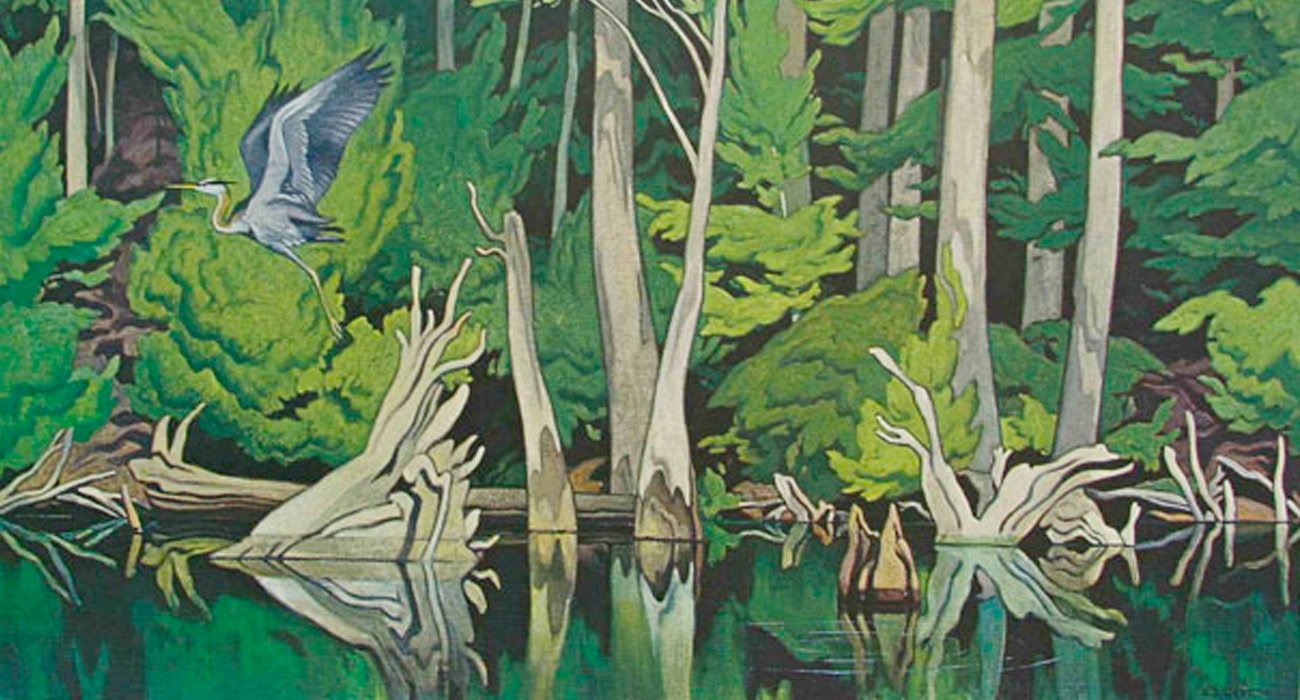

A.J. Casson, Blue Heron

Between the Body and the Breathing Earth: April 24-29, in Tuscany, Italy.

Can we replenish our capacity for joy, while renewing our solidarity with the living land? It’s hardly a simple question, for our world is rapidly becoming more dangerous. Once-hopeful democracies slide toward dictatorship, wars spread (and their attendant cruelties metastasize), the climate veers toward catastrophe. Humankind seems ever more distracted, hypnotized by our digital screens even as our fellow species tumble into extinction. At such a difficult moment in the world’s unfolding, how shall we nourish a soulful commitment to what matters?

In the course of our timed together, we’ll explore the wild ecology of perception, stirring our animal senses awake. We’ll enter into felt relation with other beings – with creatures, plants, and the elemental, earthly surroundings. Weaving contemplative encounters with nature along with rich conversation, entwining bodily gesture and movement with the arts of poetry and storytelling, the retreat will empower each of us to bring our expressive lives into a fresh and ever-evolving alignment with the more-than-human Earth.

How can we open a fresh and unshakeable solidarity between ourselves and the other animals, plants, and elemental forces that compose this breathing biosphere?

The deepening contortions of climate change – intensifying droughts, monster floods, flaring wildfires and heart-wrenching geopolitical cataclysms – all ensure that our species is tumbling toward a sea change of immense proportions. Experimenting with ideas and practices useful for grounding and thriving in dangerous times, we’ll ponder how our lives might be of genuine service to the more-than-human earth.

A dawning recognition of the power and primacy of place, an awareness of wildness unfolding wherever we turn our attention, a new humility in relation to other earthborn entities – whether salmon or cedars or storm clouds – and a radically transformed sense of the sacred: all these are struggling to be born at this teetering moment on our whirling dervish of a world. How can this altered, animistic awareness settle deep into our muscles and bones, and how can it come most powerfully to expression in our lives?

Join us for this 5-day immersive program, vivid with personal discovery and collective exploration – a gathering rich with storytelling, intellectual adventure, creaturely dynamism and heartfelt conversation. Together, we’ll pool our findings toward a new experience of the enveloping earth as an exuberant, improvisational, and sentient reality – and of ourselves as full-bodied participants (along with the humpback whales and the thrumming crickets) in the ongoing emergence of that reality.

The Alliance for Wild Ethics (AWE)

is a consortium of individuals and organizations working to ease the spreading devastation of the animate earth through a rapid transformation of culture.

A hallmark of the puzzling era we’re now living through is a remarkable juxtaposition of two apparently contrary trends. In many social circles, there exists a buoyant sense of possibility, an upbeat and expectant optimism with regard to the near and long-term future. Yet in other societal spheres, a spreading despondency weighs folks down whenever they contemplate our collective future, an overwhelming hopelessness that interferes with their ability to even envision a livable future a generation or two from now.

A hallmark of the puzzling era we’re now living through is a remarkable juxtaposition of two apparently contrary trends. In many social circles, there exists a buoyant sense of possibility, an upbeat and expectant optimism with regard to the near and long-term future. Yet in other societal spheres, a spreading despondency weighs folks down whenever they contemplate our collective future, an overwhelming hopelessness that interferes with their ability to even envision a livable future a generation or two from now.

IN THE SUMMER of 1988, I found myself kayaking in the Prince William Sound of Alaska, a few months before the undulating surface of that life-filled sea was generously layered with a glistening blanket of oil by the Exxon Corporation. A suburban kid from Long Island, this was my first time in the far north, and I was stunned by the colossal scale of the place—by immense glaciers calving off icebergs into the waters around me, by the preponderance of eagles who seemed to glare down at me from every overhanging branch and snag.

Written from within the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic:

RIGHT NOW, the earthly community of life—the more-than-human collective—is getting a chance to catch its breath without the weight of our incessant industry on its chest. The terrifying nightmare barreling through human society in these weeks has forced the gears of the megamachine (all the complex churning of commerce, all this steadily speeding up “progress”) to grind to a halt—and so, as you’ve likely noticed, the land itself is stirring and starting to stretch its limbs, long-forgotten sensory organs beginning to sip the air and sample the water, grasses and needles drinking in sky without the intermediating sting of a chemical haze.

Gusting the tops of small waves, a wind carrying salt spray collides with another thick with tree pollen; edges of both merge with a breeze plucking lichen spores from the surface of rocks as it rides up the hill where I sit, high above the coast, gazing at a far-off tanker filled with tar sands crude. Behind me, another breeze lingers at the forest edge, spiced by truck exhaust and the reek from two oyster shells broken open by a raven. I breathe in, and all those unseen currents converge, pollen and petrol fumes flooding up through my nostrils (tweaking dendrites and spreading twangs of sensation along my scalp) and then down into my chest, charging my blood and feeding the vigor in my limbs. I stretch, shoulder muscles cracking, and exhale. The feelings sparked by the sight of that tanker lend their tremor to the breath pouring out through my lips: wonder and worry texture the small vortices in front of me and the eddying flows that rush past me, informing the interference patterns between my exhalations and those of the tall cedars and the mist rising from the Salish Sea.

Abram: So often our internecine human conflicts – our readiness to take offense at perceived slights in relation to some identity or other – come in the way of and interrupt any felt discovery of our shared dependence upon the Earth, our shared interdependence with other creatures and plants and earthly elements. I often think that we use identity conflicts to hide, or avoid noticing, what’s really at stake today – which is our deeper identity as parts of Earth. There’s been so much violence toward or between or against particular groups, violations and affronts, marginalizations and erasures that must indeed be recognized, acknowledged, and – to whatever extent possible – accounted for, apologized for, even atoned for. But we do not have time for all of these affronts in their specificity to be recognized clearly before we begin noticing the collective assault – to which most if not all of us contribute – on the biosphere itself, the collective desecration of our larger Body.

In the early 1980s I was driving along a poorly paved road in the outer suburbs of New York City, my right hand fiddling with the radio dial in hopes of finding some decent songs to listen to. As the sound skidded from station to station – between the white fuzz of static and intermittent snatches of innocuous, overproduced music – I abruptly heard a clear and curious voice, not exactly singing, but definitely singsong, lilting up and down. I stopped turning the dial and just listened. At a brief station break, the woman being interviewed was identified as Joanna Macy, a Buddhist scholar and activist. And then there was that unusual voice again, breathy, with a slightly nasal twang, saying something astonishingly simple…

The Gaia hypothesis represents a unique moment in scientific thought: the first glimpse, from within the domain of pure and precise science, that this planet might best be described as a coherent, living entity. The hypothesis itself arose in an attempt to make sense of certain anomalous aspects of the Earth’s atmosphere. It suggests that the actual stability of the atmosphere, given a chemical composition very far from equilibrium, can best be understood by assuming that the atmosphere is actively and sensitively maintained by the animals, plants, oceans, and soils all acting collectively, as a vast, planetary metabolism.

Deep ecology, as a movement and a way of thinking, has commonly been contrasted to conventional environmentalism, and especially to approaches that focus only on alleviating the most obvious symptoms of ecological disarray without reflecting upon, and seeking to transform, the more deep-seated cultural assumptions and practices that have given rise to those problems.

To live is to dance with an unknown partner whose steps we can never wholly predict, to improvise within a field of forces whose shifting qualities we may feel as they play across our skin, or as they pulse between our cells, yet whose ultimate nature we can never grasp or possess in thought. To affirm our own animal existence, and so to awaken inside the world, is to renounce the pretension of a view from outside that might some day finally fathom and figure every aspect of the world’s workings. It is to acknowledge the horizon of uncertainty that surrounds any instance of knowledge, to accept that our life is at every point nourished and sustained by the mysterious.

This translation of Jean Giono’s Colline goes to press during a time of rapidly intensifying ecological disarray. More and more species find themselves shoved to the brink of the abyss by the steady surge of human progress, while seasonal cycles go haywire and the planet itself shivers into a bone-wrenching fever. Many persons find themselves bereft, astonished by the callousness of their own species and by the strange inability of modern civilization to correct its dire course. For those who recognize the animate earth as the source of all sustenance, the future—once anticipated with excitement –now looms as an inchoate shadow stirring only a vague dread. The disquiet that troubles their sleep stems less from a clear premonition than from the lack of clear images, from the difficulty of glimpsing any way toward a livable world from the place where we are now, at the end—it would seem—of a particular dream of progress.

Patricia Damery: It is a pleasure to have you with us, David, and particularly on this topic of the environment and psyche. The environmental crisis is certainly registering in the collective. The last couple of months in the San Francisco area have been very dry, as well as too warm and then too cold. It used to be that we would think this was a normal variation, but now you can feel the often unspoken question: is this a part of some larger climate change for which we are ill-prepared? Since the science is addressed elsewhere, tonight we will talk about the impact of what’s happening in the environment on all of us. I think that the environmental crisis is really a crisis of consciousness. We want to talk about what that might be, and what we might do.

In the opening pages of The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram stands in the night outside his hut in Bali, the stars spread across the sky, mirrored from below in the water of the rice paddies, and countless fireflies dancing in between. This disorientating abundance of wonder is close to what many of his readers have felt on encountering Abram’s words and his way of making sense of the world.

In order to awaken an ethical field that moves not only between ourselves and other persons, but holds sway between ourselves and the supporting earth, an eros that compels us in our interactions with the soil, the air, and the waters, and that renders our awareness susceptible to the call of other, entirely different kinds of awareness — to the call of clearcut mountainsides, and great horned owls, and salmon surging up the streams — then we shall have to begin speaking, and writing, somewhat differently. Philosophy still, by and large, speaks about the world it ponders, wielding its words as though their sounds and shapes were not a part of that breathing world, as though language were meant to get at the world from outside, rather than to invoke and to vibrate the world from within its own depths. The cool abstraction of our arguments, the rarefied terms, the lack of attention to the song of our sentences or the rhythm of our phrases, all make it obvious that, whether or not we contest the distinction between the mind and the body, we are still speaking as disembodied intellects to other bodiless intellects.

Many scientists and theorists claim that the Gaia hypothesis is merely a fancy name for a set of interactions, between organisms and their presumably inorganic environment, that have long been known to science. Every high school student is familiar with the fact that the oxygen content of the atmosphere is dependent on the photosynthetic activity of plants. The Gaia hypothesis, according to such researchers, offers nothing substantive. It is simply a new—and unnecessarily obfuscating—way of speaking of old facts. In the dismissive words of biologist Stephen Jay Gould: “the Gaia Hypothesis says nothing new—it offers no new mechanisms. It just changes the metaphor. But metaphor is not mechanism!”

Over the last two decades, as I’ve spoken with students and addressed diverse audiences regarding our human interchange with the rest of animate life, I’ve most often been challenged (and questioned) in the following manner: “Alright Abram, I understand when you say that we humans are completely embedded within a more-than-human world, and I understand your claim that many other animals, plants, and landforms are at least as necessary as humans are to the ongoing flourishing of the biosphere. But despite the attention and praise that you bestow upon other species, surely you must admit that humankind is something utterly unique in the earthly world! Isn't that obvious?”

Jeremy Hayward: Maybe we could begin by talking a little bit about animism. It seems to me that the main thing you are trying to communicate in The Spell of the Sensuous is a sense that the world is not made of dead matter—that there’s actually abundant life and intelligence everywhere.

David Abram: One of the strong intentions that moves through the book is the hope of breaking down what I see as a very artificial boundary between that which is animate and that which is inanimate, or between that which is alive and that which is not.

I very much want to suggest that everything is animate, that all things have their dynamism, that everything moves. It’s just that some things move much more slowly than other things, so we don’t notice their movement as readily. Suppose I’m walking along and a beautiful rockface draws my attention—I have a particular cliff in mind as I’m saying this— and I find myself moved by this presence, by this rock, by this huge implacable force that captures me each time I walk near it. If I’m moved by this being, how can I say that it does not move? By insisting that the rock itself does not move I’m denying my own direct experience.

What a pleasure to have this chance to ponder this marvelous, and marvelously strange, poem cycle — “Mountains and Rivers Without End”— by our friend Gary Snyder.

I must admit the poem has had me flummoxed and befuddled. Yet I was immediately taken with the animistic terrain of these pages. This shifting, metamorphic realm where everything is alive — not just mountains and rivers, but everything. Not only bristlecone pines, and mountain sheep, but also office buildings, and objects — even a sag-assed rocking chair in the basement of Goodwill has its own struggling life. Of course, all the cultures that we know of that are thoroughly and deeply animistic in this way, for whom everything is alive and everything speaks, are oral, non-writing cultures. So I want to reflect a bit on the ways that Gary’s work, and this very literate poem in particular, aims us toward a renewal of oral culture.

David Abram: Hi, David! Here I am at last. My sweetheart and I have been wandering through the American West, snooping around for a potential community, and although no place reached up through our feet and grabbed us, we’ve landed for a time in the high desert of northern New Mexico—in the midst of a mongrel community of activists I know fairly well from years spent living and loving in this dusty terrain before moving to Washington State three years ago. We had hoped that island realm would claim us, but the combined effects of Boeing, Microsoft, and the city of Seattle generally sprawling all around us, sprawling up into our noses and our ears, finally forced us to flee. We embarked on this most futile of quests in turn-of-the-millennium America: the quest for wildness—wildland and wild, earthy, close to the ground community. Slim pickin’s these days. Development everywhere, clearcuts even in the back of the backcountry, streams ravaged by effluent from abandoned mining operations. It’s not all hopeless: there’s still plenty mystery out in them thar hills, but I was mostly shocked by how the same all the towns are becoming. Ah well . . . I suppose Canada’s a decade or two behind the States, and if only we could get visas to live and work in Canada, we prob’ly be there in a flash.

Derrick Jensen: I’d like to start with two questions that might actually be one. They are: Is the natural world alive? And second, what is magic?

David Abram: Is there really anything that is not alive? Certainly we are alive, and if we assume that the natural world is in some sense not alive, it can only be because we think we’re not fully in it, and of it.

Actually, it’s difficult for me to conclude that any phenomenon I perceive is utterly inert and lifeless; or even to imagine anything that is not in some sense alive, that does not have its own spontaneity, its own openness, its own creativity, its own interior animation, its own pulse — although in the case of the ground, or this rock right here, its pulse may move a lot slower than yours or mine.

Now your other question: What is magic? In the deepest sense, magic is an experience. It’s the experience of finding oneself alive within a world that is itself alive. It is the experience of contact and communication between oneself and something that is profoundly different from oneself: a swallow, a frog, a spider weaving its web…

Resolution From NABC II

We resolve that NABC III recognize four participants to represent the interests and perspective of our non-human cousins:

One for our four-legged and crawling cousins, One for those who swim in the waters, One for the winged beings, the birds of the air, and One very sensitive soul for all the plant people.

Other participants who wish to keep faith with other species are welcome; however, those four individuals formally recognized to act as all-species representatives will not participate in any other capacity during the time that they function as representatives. Their role in the Congress is partly one of deep stillness, of being profoundly awake, of keeping faith with those beings not otherwise present within the circles.

By providing a new way of viewing our planet—one that connects with some of our oldest and most primordial intuitions regarding the animate Earth—Gaia theory ultimately alters our understanding of ourselves, transforming our sense of what it means to be human. For much of the modern era, earthly nature was spoken of as a complex yet mechanical clutch of processes, as a deeply entangled set of objects and objective happenings lacking any inherent life, or agency, of its own. Such a conceptual regime helped sustain the cool detachment that was generally deemed necessary to the furtherance of the natural sciences. Yet the thorough objectification of nature also served to underwrite the sense of human uniqueness that has permeated the modern era. As long as the Earth had no unitary life, no agency, no subjectivity of its own, then we humans could continue to ponder, analyze, and manipulate the natural world as though we were not a part of it; our own sentience and subjectivity seemed to render us outside observers of this curious pageant, overseers of nature rather than full participants in the biotic community. The thoroughgoing objectification of the Earth thus enabled the old, theological presumption—that the Earth was ours to subdue and exploit for our own, exclusively human, purposes—to survive and to flourish even in the modern, scientific era. Gaia theory, however, gradually undoes this age-old presumption.

Slowly, inexorably, members of our species are beginning to catch sight of a world that exists beyond the confines of our specific culture—beginning to recognize, that is, that our own personal, social, and political crises reflect a growing crisis in the biological matrix of life on the planet. The ecological crisis may be the result of a recent and collective perceptual disorder in our species, a unique form of myopia which it now forces us to correct. For many who have regained a genuine depth perception — recognizing their own embodiment as entirely internal to, and thus wholly dependent upon, the vaster body of the Earth — the only possible course of action is to begin planning and working on behalf of the ecological world which they now discern.