In the Ground of our Unknowing

Originally published on April 7, 2020 in Emergence Magazine - written in the earliest weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

An audio version of this essay is available here, narrated by David Abram.

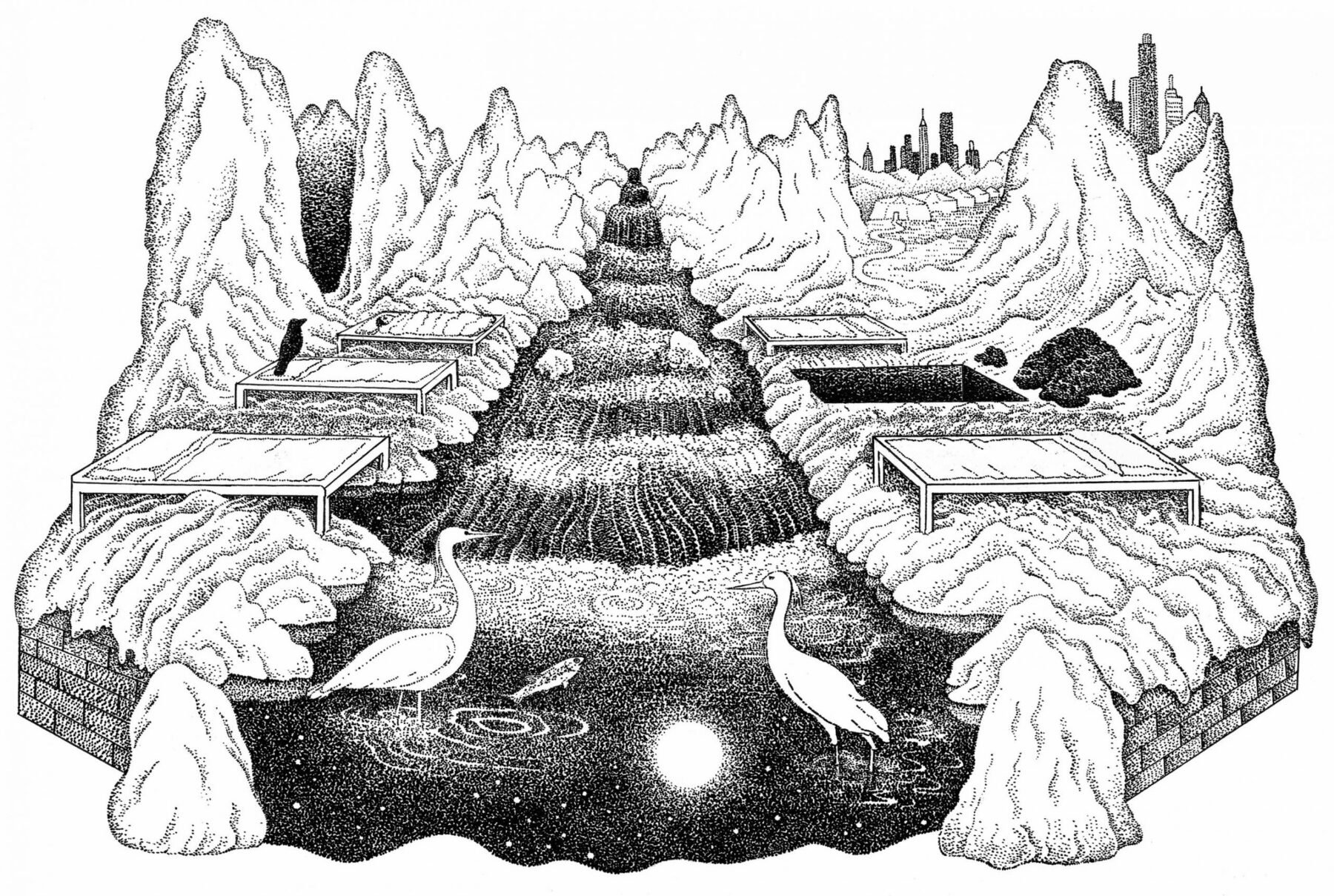

Illustration by Lina Müller and Luca Schenardi

Facing the paradoxes and ambiguities enmeshed with the COVID-19 pandemic, David Abram finds beauty in the midst of shuddering terror. As we’re isolated in this uncertain time, he writes, we can turn to the more-than-human world to empower our empathy for each other.

RIGHT NOW, the earthly community of life—the more-than-human collective—is getting a chance to catch its breath without the weight of our incessant industry on its chest. The terrifying nightmare barreling through human society in these weeks has forced the gears of the megamachine (all the complex churning of commerce, all this steadily speeding up “progress”) to grind to a halt—and so, as you’ve likely noticed, the land itself is stirring and starting to stretch its limbs, long-forgotten sensory organs beginning to sip the air and sample the water, grasses and needles drinking in sky without the intermediating sting of a chemical haze. The reports of abundant fish returning to the effluent-clogged canals of Venice may not be true—mostly, it seems, the usual murkiness of the canals is clearing due to the circumstance that ceaseless boat traffic is not churning up those waterways, and so it’s become possible, for the first time in ages, to glimpse schools of fish who’ve always been there swimming through the suddenly pellucid waters. But if we can see those fish in the long quiet of these days, then those finned beings can also see us, can see the sun and the gleaming moon in ways they’ve not been able to for decades. Gray Whales and Humpbacks in the Pacific Northwest can suddenly hear one another’s hundred-mile songs and calls echoing through the depths, uninterrupted by the incessant mechanical whine of boat engines—since the whale-watching tours that hound them have stopped indefinitely, as have the growling propellers of cruise ships and the whirring of most pleasure boats (an underwater cacophony that’s been steadily intensifying over the years, monopolizing the exquisite auditory conductance of the aquatic realm, and confounding all those who communicate in buzzing blips and pings and singsong descants through the fluid medium).

Just as, in multiple cities, the profusion of birdsong is becoming evident, no longer hidden by ringtones, honking horns, piercing car alarms, and people yelling into their phones (by all the giddy roiling thrum of business as usual).

And right now, late at night, a child is stepping outside her home in the suburbs of Shanghai—as another child is doing in Mumbai, and another in Madrid just before dawn. The child in Shanghai is walking the family dog with her father. The girl stretches her cramped limbs, leaning her head back—whereupon she notices something surpassingly strange. Her eyes widen in wonder: a glimmering river of light is coursing above the silhouetted buildings! Numberless points of light (she knows they are stars) gleam and wink at her along the margins of the overhead river, while near the central current those lights seem to fold into a churning froth of bright cloud. “What is that?” she asks her father. He follows her gaze upward. “Oh,” he says, “that’s the Silver River.…”

In Mumbai, the boy’s grandmother says, “Oh c’mon, you know that: that’s the Ganges of the Aether.”

In Madrid, the father looks up, and then replies to his son: “That’s the Milky Way. Don’t you remember learning about it?” “Yeah…,” the boy answers. “I just didn’t know that you could actually see it.” The father looks back up, then removes his glasses. They both stare and stare.

LUMINOUS BEAUTY IN the midst of shuddering terror. Interpersonal solidarity—layer upon tearful layer of empathy for one another—in the midst of enforced solitude and loneliness. The paradoxical, ambiguous nature of this moment is so confounding, so bewildering! I mean, how excellent that our arrogant species receives this collective slap-in-the-face reality check, waking us two-leggeds up to the simple truth that we are not at all in control, have never really been in control, that we live at the behest of powers—of a complex interplay of powers—far beyond our ability to fully fathom, to predict, or to steer. What hubris to have imagined we could do whatever we want with this exquisitely interwoven wonder of a world! And yet how awful that this lesson must come at the expense of so many unsuspecting human lives, so many innocent souls now shivering with fever and fright as they struggle to draw breath.

Here’s another ambiguity. We’re finally being forced to recognize that no top-down institution, governmental or otherwise, can fully ensure our safety. That our deepest insurance against disaster is going local—by getting to know our actual neighbors and checking in on one another when we can, participating in our local community and apprenticing with the more-than-human terrain that surrounds and sustains us. Eating more of what grows locally, and learning to grow some of these foods ourselves, reduces the long supply chains that bring not just foods and products from far-flung places into our lives, but also pathogens that would otherwise be way more limited in their circulation. Here in northern New Mexico, youth climate activists have in the last two weeks established a thriving and rapidly growing mutual aid system, whereby individuals are offering all sorts of gifts and skills to the wider community, wherein anyone can request needed help and be matched, fairly quickly, with someone providing those skills free of charge. In fact, by the time of this writing (in late March) analogous place-based mutual aid initiatives are sprouting up in localities pretty much everywhere around the world—wild harvesting needed herbs, providing childcare for doctors, delivering food and pharmaceuticals and equipment, offering skilled counseling (by phone) for folks freaking out, setting up sanitation systems in rural areas with scant water, handcrafting masks and protective gear. What a wonder! Yet at this same moment, the very same catastrophe that’s teaching us to bring our attention back to the local and nearby, forces us to take distance from every person in our vicinity, and to connect only via the most mediated and disembodied of ways, speaking only via the phone and the computer, exchanging information via FaceTime and Zoom and Twitter.

Even a neo-Luddite like me has to admit that the online and internet world has become a huge boon and blessing in this tenuous time! And of course even before the pandemic, the digital sphere was enabling crucial and unexpected alliances to spark up and proliferate under the radar, empowering vital mobilizations to crystallize long before top-down powers could catch sight of and try to quash them. Yet the internet has also enabled the consolidation and widespread organization of many insidious impulses as well, including the most sociopathic forms of fearmongering and scapegoating (to say nothing of the limitless capacity for personal data harvesting and surveillance that the internet offers, free of charge, to transnational corporations). In their enthusiasm for the wired world, many commentators have been saying, “Wow, the coronavirus is a fast track to the future! Once we see that we can enact much of our lives online, why should we go back to doing things in the far less efficient world of flesh-and-blood interactions?” In The New York Times, one columnist suggested that once we’ve learned how to conduct most college courses over the internet, why would we ever want to go back to sitting and lecturing in classrooms? Meanwhile, my son in tenth grade is jumping out of his skin with boredom at the doldrum dullness of screen-imprisoned classes, and my daughter—abruptly forced home from her blissful freshman year at college—is despairing at the drab inanity of college seminars without the delicious bustle of seeing, hearing, and especially feeling her classmates as they reflectively tussle with one another and with the professor while puzzling out problems together. She’s missing the (let’s face it) erotic goodness of real learning that happens in direct physical interchange with one another, when so much of what is really discovered happens at a bodily-felt level below the strictly cognitive layer of the words. The completely conscious layer of learning rides on that depth like ripples on the surface of the sea. Wisdom arises—whether within a student or a teacher, or within the awareness of an entire class—when the verbal, cognitive layer of learning is awake to its rootedness in the emotionally charged dimension of our corporeal and intercorporeal life with one another, in the palpable rooms and landscapes we inhabit together.

So while I trust that there’s a lot we’ll be learning from the strangeness of these days in enforced isolation from each other, I sure hope that we’ll not be drawing upon this time to swivel huge swaths of our public and private life permanently into the virtual sphere, away from the necessarily fraught and vulnerable world of fleshly encounter in the thick of the sensuous—which, I hasten to add, is the only world that we share with the other animals, the plants, and the blustering winds. I mean, do we really wish to render education even more abstract and aloof from the perspectives of other creatures, from the intricately entangled wetlands and rivers, from the many-voiced forests with whom we share this round world? Do we really need to render ourselves still more oblivious to the reality of other, nonhuman lives? If so, then by all means let’s all pile online, and look to conduct more and more of our lives in virtual spaces.… But the cascading catastrophes of climate change, and our apparent inability (or unwillingness) to alter our lives in response to those cataclysms, suggest that it might be salutary for us to replenish our direct, sensorial contact with the wider community of beings wherever we live. We might wish to reacquaint ourselves with the other denizens of our locale.

After all, while this plague enforces a temporary distance from other humans, there is no reason not to lean in close to other beings, gazing and learning—for instance—the distinguishing patterns of the bark worn by each of the local tree species where you live. No reason not to step outside and pry open your ears, listening and learning by heart the characteristic songs and calls of the various local birds; no reason not to apprentice yourself to a spider as it weaves its intricate web in front of the porchlight. Or to practice recognizing and naming—as I have been—the different types of clouds that are conjured out of the blue by the scattered mountains in this region, the wispy brushstrokes and phantom ridges and clumped clusters that congregate and dissipate in the high desert sky. Estranged from direct human contact for a brief while, we’ve a chance to open a new intimacy with the wider world we’re a part of, with coyote and owl and aspen. Soon enough, if it’s not already happening where you are, spring will be exploding out of all those budded branches. And that is a goodness. If you live anywhere near a wetland, pay it an evening visit—see if you can join your voice to the gurgling chorus of frogs without shocking them all into silence (it takes practice, sure, but I promise it’s doable).

Sit down for tea with a lichen-encrusted boulder. Excellent. Now get over your shyness, wander over to the bank of the river that courses through your town, and invite the gushing current to dance with you. If it accepts, you needn’t plunge in (maybe save that for the summer), but rather gaze and listen and feel into the flux as you move—let its wildness tumble downstream through your muscles, coaxing the river into rapport with your own sinuous moves and meanders, experimenting till you find the right rhythm, the right syncopation for the erotic rock and roll of its alluvial groove.

Sure, it’s mighty important to keep apprised of the human news. Yet we can draw unexpected nourishment by walking away, now and then, from the screen-mediated sphere of our exclusively human concerns, rekindling our animal senses and rediscovering our solidarity with everything else.

SO SOME OF us are now learning to listen in to and maybe even converse with the elemental utterances of things that don’t speak in words, tuning our ears and our skin to the discourse of multiple other-than-human beings: each redwing blackbird or storm cloud or naked chunk of sandstone jostling with the rest of existence. And every one of us is now shuddering with inadvertent creaturely empathy at what’s befalling so many of our human sisters and brothers who abruptly find themselves unable to draw breath, their lungs ravaged, their bodies cut off by plastic enclosures and pumps from the touch or even the sight of their loved ones.

We breathe for each other. We feel each other’s feelings shuddering through us—we cannot help but do so! Yet is this because we’re all human, because we share a basic commonality of body and mind, because our species has its own autonomy and autonomous integrity, such that all of Humankind is a single collective Body that flexes and reverberates in each one of us?

Such is our common assumption, but actually … no, I don’t think so. If we consider the extant and far-flung span of our collective human flesh—if we consider the actual spatial shape of this hopelessly spread out thing we call humankind, we will notice, I think, that its shape is that of a sphere. Because it is the vast and spherical Earth that gives us our actual shape and coherence as a species.

And if we ponder the activity of any individual human at this very moment, we’ll notice that he or she or they are breathing (or struggling to breathe)—each of us drinking this unseen elixir that’s granted to us, ceaselessly—by the innumerable rooted, leafing, needled, stemmed, trunked, or algal beings that are also breathing in our vicinity. We have no autonomy, no integrity as a species separate from the other species of this world, no collective existence as a creature apart from the animate Earth. We can understand ourselves, and feel what it is to be human, only through our interaction and engagement with all these other, nonhuman beings with whom our lives are so thoroughly tangled. And yes, of course we can and indeed do feel a deep solidarity with one another, and with the rest of our kind. Yet we cannot stretch that bodily empathy out to all of our single species except by way of the more-than-human Earth. We cannot extend our senses to the whole of humankind without the sensitive and sentient Earth getting us there. It is this vast and sensitive sphere, glimmering with sensations, that grants us that ability to feel and resonate with one another, to ache when another aches—whether it be a small girl hospitalized in Iran or a young elephant whose mother was killed by poachers, whether an old man struggling to breathe in China or an aging sea lion snagged and tangled in a fishing net. Our real collective Flesh is not that of “humankind” as an autonomous abstraction, but is the living Body of this biosphere, breathing. That’s us.

STILL, THERE’S THE rising tide of human happenings reaching us through the media, much of it sad beyond reckoning. One massive matter that this virus is abruptly making visible, for those who couldn’t or wouldn’t see it before is the dumbfounding injustice—the outrageous coldheartedness—of the way our societies are currently structured, such that some persons seem always able to avail themselves of protection from the devastation of illness (having ready access to tests, and fine doctors, and all the necessary machinic support) while crowds of others are tossed aside or treated grotesquely. Like the undocumented immigrants currently crammed into overcrowded detention centers here in the US: how can we keep the virus from running rampant in such spaces? Or overseas: how can we protect, from the spreading contagion and death, countless half-starved Syrian refugees now stranded and stateless? Or the laid off workers in India now trying to make their way back to their rural villages in overstuffed buses or on foot through a gauntlet of regulations and club-wielding police? And here at home: how can we protect our brothers and sisters doing time in private, for-profit prisons without even minimally adequate sanitation? Or the many who are homeless and destitute, usually through no fault of their own?

Healthcare, as both Sanders and Warren proclaimed over and over, ain’t a privilege: it’s a basic human right. We instinctively feel that everyone deserves respect and the right to live out their days, that no human should have to forfeit their life simply because they’ve only ever earned minimum wage, or due to their skin color, or their age, or their refugee status. But as this pandemic swells and breaks like a colossal tsunami across the land, it strips away the flimsy facades, exposing all the god-awful structural violence of this winner-take-all society, leaving most of us feeling astonished and ashamed that we could have allowed such hideous disparities to grow and grow without struggling steadily to rectify them.

I reckon we’ll no longer be able to easily hide or paper over much of this structural violence after the virus has had its way with us. At least I pray that we won’t. We will have to change. In ever so many ways, we’ll have to change. (Dear Gaia, let us PLEASE not go back to fucking “normal.”) But what shape, what mode will the changes take? Will we simply go back to the rickety Rube Goldberg contraption of “Obamacare” and just extend it to cover a few more people? Might we begin to notice that a person’s health depends on having a range of real relationships, on face-to-face community, on reciprocity with a robust and flourishing ecology? Or will we strive now to make our lives ever more antiseptic, engaging not only our social interactions but more and more of our education online, so we’ll not have to risk contamination through physical contact—so we’ll not have to tangle with the always unpredictable muck of the real? Will we all be so desperate to have everything go back to “normal” that we’ll rev and rev and ramp back up our overly addicted fossil-fueled economy, injecting gobs of crude oil back into our veins like strung out junkies, throwing the megamachine into overdrive? And in this way consign our own and every other remaining species—those we’ve not already crowded and kicked over the brink of extinction—to the irreversible hell of runaway climate change?

Or will we recognize the coronavirus as a fierce but relatively gentle harbinger of something far more calamitous, a teacher kindly sent to slap us awake to our actual circumstances?

Much that influences the future shape of our societies will ride on how we emerge from this crisis—assuming we do emerge—how we transition out of the strangely suspended dreamscape in which we suddenly find ourselves adrift. Governments and their administrative agencies will play their roles as best they can, each trying to claw or engineer its way back into the daylit realm. But the textures and tastes that eventually come to predominate, the rhythms of community in our bioregion, the generosity and convivial ethos of the larger body politic—or the robotic and bureaucratic rigidity of that body politic—will to a large extent be determined by the choices each of us makes in this cocoon-like, shape-shifting moment. The future will be sculpted, that is, by the elemental friendships and alliances that we choose to sustain us, by our full-bodied capacity for earthly compassion and dark wonder, by our ability to listen, attentive and at ease, within the forest of our unknowing.